American Kestrels - A cavity nesters In Decline

Credits http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birding/american-kestrel/

The Bluebird Society of Pennsylvania is concern of all Cavity Nesters. Especially when they are in decline. We realize this beautiful bird can be a natural predator of the bluebirds but that does not prevent our organization to come to its aid. If you own farm land, wooden acreage you can come to the aid of these small like falcons. They really are a beneficial bird to have around. Please read below facts concerning the American Kestrels.

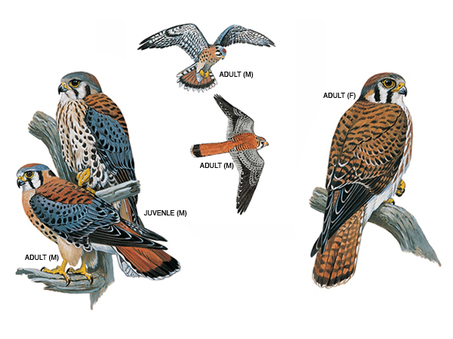

North America’s littlest falcon the American Kestrel packs a predator’s fierce intensity into its small body. It's one of the most colorful of all raptors: the male’s slate-blue head and wings contrast elegantly with his rusty-red back and tail; the female has the same warm reddish on her wings, back, and tail. Hunting for insects and other small prey in open territory, kestrels perch on wires or poles, or hover facing into the wind, flapping and adjusting their long tails to stay in place. Kestrels are declining in parts of their range; you can help them by putting up nest boxes.

It can be tough being one of the smallest birds of prey. Despite their fierce lifestyle, American Kestrels end up as prey for larger birds such as Northern Goshawks, Red-tailed Hawks, Barn Owls, American Crows, and Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s Hawks, as well as rat snakes, corn snakes, and even fire ants.

It can be tough being one of the smallest birds of prey. Despite their fierce lifestyle, American Kestrels end up as prey for larger birds such as Northern Goshawks, Red-tailed Hawks, Barn Owls, American Crows, and Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s Hawks, as well as rat snakes, corn snakes, and even fire ants.

- In winter in many southern parts of the range, female and male American Kestrels use different habitats. Females use the typical open habitat, and males use areas with more trees. This situation appears to be the result of the females migrating south first and establishing winter territories, leaving males to the more wooded areas.

- Unlike humans, birds can see ultraviolet light. This enables kestrels to make out the trails of urine that voles, a common prey mammal, leave as they run along the ground. Like neon diner signs, these bright paths may highlight the way to a meal—as has been observed in the Eurasian Kestrel, a close relative.

- Kestrels hide surplus kills in grass clumps, tree roots, bushes, fence posts, tree limbs, and cavities, to save the food for lean times or to hide it from thieves.

- Habitat - Open Woodland

American Kestrels favor open areas with short ground vegetation and sparse trees. You’ll find them in meadows, grasslands, deserts, parks, farm fields, cities, and suburbs. The southeastern U.S. form breeds in unusual long leaf pine sand hill habitat. When breeding, kestrels need access to at least a few trees or structures that provide appropriate nesting cavities. American Kestrels are attracted to many habitats modified by humans, including pastures and parkland, and are often found near areas of human activity including towns and cities.

Food - Insects

American Kestrels eat mostly insects and other invertebrates, as well as small rodents and birds. Common foods include grasshoppers, cicadas, beetles, and dragonflies; scorpions and spiders; butterflies and moths; voles, mice, shrews, bats, and small songbirds. American Kestrels also sometimes eat small snakes, lizards, and frogs. And some people have reported seeing American Kestrels take larger prey, including red squirrels and Northern Flickers.

Nesting Facts - Clutch Size 4–5 eggs - Number of Broods 1-2 broods - Egg Length 1.2–1.5 in 3–3.8 cm - Egg Width 0.9–1.1 in

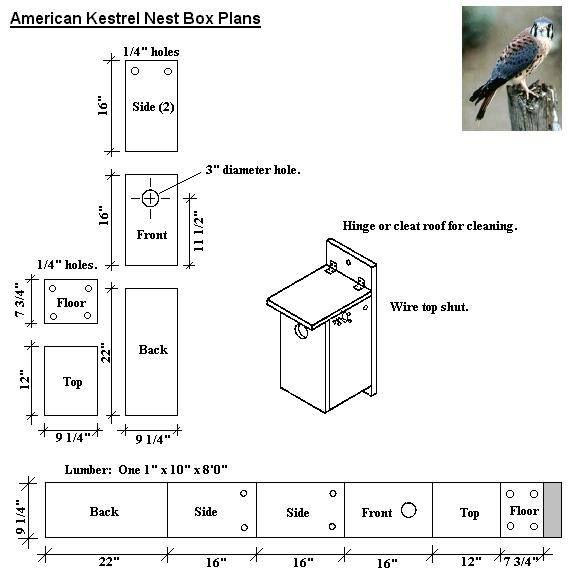

2.4–2.8 cm - Incubation Period 26–32 days - Nestling Period 28–31 days - Egg Description White to yellowish or light reddish-brown, mottled with violet-magenta, gray, or brown .Condition at Hatching Feeble, with sparse white down over pinkish skin; eyes partially open by first or second day. - Nest Description - American Kestrels do not use nesting materials. If the cavity floor is composed of loose material, the female hollows out a shallow depression there. American Kestrels nest in cavities, although they lack the ability to excavate their own. They rely on old woodpecker holes, natural tree hollows, rock crevices, and nooks in buildings and other human-built structures. The male searches for possible nest cavities. When he’s found suitable candidates, he shows them to the female, who makes the final choice. Typically, nest sites are in trees along wood edges or in the middle of open ground. American Kestrels take readily to nest boxes.

- Behavior - Soaring

American Kestrels normally hunt by day. You may see a kestrel scanning for prey from the same perch all day long—or changing perches every few minutes. A kestrel pounces on its prey, seizing it with one or both feet; the bird may finish off a small meal right there on the ground, or carry larger prey back to a perch. During breeding season, males advertise their territory by repeatedly climbing and then diving, uttering a short series of klee! calls at the top of each ascent. Courting pairs may exchange gifts of food; usually the male feeds the female. Early in the pairing-up process, groups of four or five birds may congregate. You may see American Kestrels harassing larger hawks and eagles during migration, and attacking hawks in their territories during breeding season. Kestrels compete over the limited supply of nesting cavities with other cavity-nesters, and sometimes successfully fight off or evict bluebirds, Northern Flickers, small squirrels, and other competitors from their chosen sites. Although this is still the continent’s most common and widespread falcon, the American Kestrel is declining. Land clearing during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries probably raised American Kestrel numbers substantially. By the 1980s there were an estimated 1.2 million kestrel pairs in North America. Modern-day declines stem from continued clearing of land and felling of the standing dead trees these birds depend on for their nest sites. The American Kestrel is also losing prey sources and nesting cavities to so-called “clean” farming practices, which remove hedgerows, trees, and brush. An additional threat is exposure to pesticides and other pollutants, which can reduce clutch sizes and hatching success. For kestrels in North America, a larger problem with pesticides is that they do their job, destroying the insects, spiders, and other prey on which the birds depend. - Credits ;

- Smallwood, J. A., and D. M. Bird. 2002. American Kestrel (Falco sparverius). InThe Birds of North America, No. 602 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America Online, Ithaca, New York.

- Dunne, P. 2006. Pete Dunne's Essential Field Guide Companion. Houghton Mifflin, New York.

- Elphick, C., J.B. Dunning, Jr., and D.A. Sibley. 2001. National Audubon Society Guide to Bird Life & Behavior. Alfred A. Knopf, New York..

HOW AND WHEN DO I INSTALL MY KESTREL NEST BOX?

Install boxes no later than the end of February. Boxes should be placed in areas surrounded by at least 1 acre of open habitat in a larger area of approximately 50 acres of primarily open landscape and as far away from woodlots as possible. Place them in open grassy areas away from woodland edges to reduce use by non-target bird species, squirrels and Cooper’s Hawks. Nest boxes should be placed at least 1/2 mile apart. Install the boxes 10-20 feet up from the ground on a tree, post, out-building, barn, or other structure. Orient the box with a southern exposure to aid in thermoregulation and help prevent starlings from using the box. Place wood chips in the box.

WHY DO WE NEED TO MONITOR?

Monitoring kestrel boxes allows the observer to prevent non-target species using the boxes, documents that kestrels are using the box, and determines whether or not young fledge.

MONITORING - When and How do I monitor my Kestrel Nest Box?

Monitoring should begin between March 1st and March 15th and continue through June. If a pair of kestrels nests later into the season, continue monitoring it beyond the end of June. Monitor the boxes weekly. Early in the breeding season kestrels may not be present, but monitoring is necessary to make sure that starlings or other species, like mice or squirrels, do not use the box. If another species other than kestrels is observed using the box, get a ladder, open the box, clean it out and replace the wood chips. Be ready for the inhabitant to exit when you open the box or gently tap the box before opening it. If other native bird species such as Eastern Screech Owls or Eastern Bluebirds use the box don’t disturb them and allow them to continue using the box. Hopefully you will start to see a pair of kestrels using the box or even a male bringing food to a female. After a pair is observed using the box, continue visiting weekly to document nesting status using the data sheet to document your observations. Observations should be made between mid-morning and late afternoon for 15 to 30

minutes, from March through late June or until the box is no longer being used by kestrels. Select a viewing location that allows you to see the nest box and the surrounding area clearly. Be sure to inspect nearby power lines, fences, and trees, where kestrels often perch, nesting kestrels frequently enter and exit nest boxes by both the male and female. After about 30 days from when nesting began, the eggs

should hatch. Females tend to be the primary brooder until a week after the eggs hatch and so the male may may be seen more frequently during this stage. After that point, you are likely to see both parents since both bring food to the young. The young will fledge about 30 days after hatching. The young are dependent on their parents for 12-14 days after fledging and the entire family may be seen in the

surrounding area during this period. A final visit should occur one month after the nestlings have fledged to clean the nest box of all materials. Leave boxes out during the winter to provide winter cover for kestrels, screech owls, and other resident birds.

Credits - Audubon Society New York http://ny.audubon.org/

Install boxes no later than the end of February. Boxes should be placed in areas surrounded by at least 1 acre of open habitat in a larger area of approximately 50 acres of primarily open landscape and as far away from woodlots as possible. Place them in open grassy areas away from woodland edges to reduce use by non-target bird species, squirrels and Cooper’s Hawks. Nest boxes should be placed at least 1/2 mile apart. Install the boxes 10-20 feet up from the ground on a tree, post, out-building, barn, or other structure. Orient the box with a southern exposure to aid in thermoregulation and help prevent starlings from using the box. Place wood chips in the box.

WHY DO WE NEED TO MONITOR?

Monitoring kestrel boxes allows the observer to prevent non-target species using the boxes, documents that kestrels are using the box, and determines whether or not young fledge.

MONITORING - When and How do I monitor my Kestrel Nest Box?

Monitoring should begin between March 1st and March 15th and continue through June. If a pair of kestrels nests later into the season, continue monitoring it beyond the end of June. Monitor the boxes weekly. Early in the breeding season kestrels may not be present, but monitoring is necessary to make sure that starlings or other species, like mice or squirrels, do not use the box. If another species other than kestrels is observed using the box, get a ladder, open the box, clean it out and replace the wood chips. Be ready for the inhabitant to exit when you open the box or gently tap the box before opening it. If other native bird species such as Eastern Screech Owls or Eastern Bluebirds use the box don’t disturb them and allow them to continue using the box. Hopefully you will start to see a pair of kestrels using the box or even a male bringing food to a female. After a pair is observed using the box, continue visiting weekly to document nesting status using the data sheet to document your observations. Observations should be made between mid-morning and late afternoon for 15 to 30

minutes, from March through late June or until the box is no longer being used by kestrels. Select a viewing location that allows you to see the nest box and the surrounding area clearly. Be sure to inspect nearby power lines, fences, and trees, where kestrels often perch, nesting kestrels frequently enter and exit nest boxes by both the male and female. After about 30 days from when nesting began, the eggs

should hatch. Females tend to be the primary brooder until a week after the eggs hatch and so the male may may be seen more frequently during this stage. After that point, you are likely to see both parents since both bring food to the young. The young will fledge about 30 days after hatching. The young are dependent on their parents for 12-14 days after fledging and the entire family may be seen in the

surrounding area during this period. A final visit should occur one month after the nestlings have fledged to clean the nest box of all materials. Leave boxes out during the winter to provide winter cover for kestrels, screech owls, and other resident birds.

Credits - Audubon Society New York http://ny.audubon.org/

Red-Headed Woodpecker - A cavity nesters in Decline. And you can Help by building a nest box. see below!

Red- Headed Woodpecker

Red- Headed Woodpecker

The Red-headed Woodpecker, Melanerpes erythrocephalus, is a medium-sized woodpecker, about the size of a robin.They breed in semi-open country across southern Canada and the eastern-central United States. Red-heads excavate nests in dead trees, or often in dead limbs of living trees high off the ground. Red-heads often occur in loose colonies or clusters. If there is good habitat, many breeding pairs may be found in the same area. Even in clusters, birds remain territorial and do not cooperate.Northern birds will migrate to the southern parts of the range; southern birds are often permanent residents.

Red-heads are opportunistic feeders. In summer, they will fly to catch insects in the air or on the ground. Through the fall they will gather and store nuts. They are omnivorous, eating insects, seeds, fruits, berries and nuts.

Once abundant, populations have declined by 89% since 1967. This is partly due to increased nesting competition from starlings and collisions with cars. Mainly declines are due to overall loss of habitat and especially loss of dead trees and trees with large dead limbs. Dead branches are excavated for nests, roost and food caches.

Many Northeastern states no longer have nesting Red-headed Woodpeckers.

Best Management Practices for Private Landowners

Whether a hunter, farmer or homeowner, you may own a piece of land that can be used by red-heads. If you have large trees on your lot, keep them. If the trees have dead branches or have themselves died, leave some for a few years. Red-headed Woodpeckers can respond within one year to suitable habitat!

Educate yourself and your neighbors to the red-head's habitat needs. You may be richly rewarded.

Ideal Red-headed Woodpecker habitat includes:

The recovery of the red-head calls for a more measured approach. If it's safe to leave a wildlife tree up for a few years, consider doing so. If a small stand of trees is killed due to flood, drought or other cause, think of it as a nursery for red-heads and other wildlife.

Please contact us with any questions. We can work with you to assess the potential for your site and we're happy to supply additional information. Credits to the above information and further assistance can be found at redheadedrecovery.org.

Red-heads are opportunistic feeders. In summer, they will fly to catch insects in the air or on the ground. Through the fall they will gather and store nuts. They are omnivorous, eating insects, seeds, fruits, berries and nuts.

Once abundant, populations have declined by 89% since 1967. This is partly due to increased nesting competition from starlings and collisions with cars. Mainly declines are due to overall loss of habitat and especially loss of dead trees and trees with large dead limbs. Dead branches are excavated for nests, roost and food caches.

Many Northeastern states no longer have nesting Red-headed Woodpeckers.

Best Management Practices for Private Landowners

Whether a hunter, farmer or homeowner, you may own a piece of land that can be used by red-heads. If you have large trees on your lot, keep them. If the trees have dead branches or have themselves died, leave some for a few years. Red-headed Woodpeckers can respond within one year to suitable habitat!

Educate yourself and your neighbors to the red-head's habitat needs. You may be richly rewarded.

Ideal Red-headed Woodpecker habitat includes:

- Large trees. These may be hardwoods or pines. Red-heads are very opportunistic.

- A park-like low density of trees. City lots and pastures are ideal.

- An open understory.

- A good number of mast trees, producing nuts and acorns. Oaks, hickory, beech. While red-heads eat insects in the warmer months, these nut trees will help them through the colder months.

- Good availability of trees with dead limbs or dead trees. That is, "wildlife trees".

The recovery of the red-head calls for a more measured approach. If it's safe to leave a wildlife tree up for a few years, consider doing so. If a small stand of trees is killed due to flood, drought or other cause, think of it as a nursery for red-heads and other wildlife.

Please contact us with any questions. We can work with you to assess the potential for your site and we're happy to supply additional information. Credits to the above information and further assistance can be found at redheadedrecovery.org.

Cool Facts

Habitat

Open Woodland

Red-headed Woodpeckers breed in deciduous woodlands with oak or beech, groves of dead or dying trees, river bottoms, burned areas, recent clearings, beaver swamps, orchards, parks, farmland, grasslands with scattered trees, forest edges, and roadsides. During the start of the breeding season they move from forest interiors to forest edges or disturbed areas. Wherever they breed, dead (or partially dead) trees for nest cavities are an important part of their habitat. In the northern part of their winter range, they live in mature stands of forest, especially oak, oak-hickory, maple, ash, and beech. In the southern part, they live in pine and pine-oak. They are somewhat nomadic; in a given location they can be common one year and absent the next.

Food

Omnivore

Red-headed Woodpeckers eat insects, fruits, and seeds. Overall, they eat about one-third animal material (mostly insects) and two-thirds plant material. Their insect diet includes beetles, cicadas, midges, honeybees, and grasshoppers. They are one of the most skillful flycatchers among the North American woodpeckers (their closest competition is the Lewis’s Woodpecker). They typically catch aerial insects by spotting them from a perch on a tree limb or fencepost and then flying out to grab them. Red-headed Woodpeckers eat seeds, nuts, corn, berries and other fruits; they sometimes raid bird nests to eat eggs and nestlings; they also eat mice and occasionally adult birds. They forage on the ground and up to 30 feet above the forest floor in summer, whereas in the colder months they forage higher in the trees. In winter Red-headed Woodpeckers catch insects on warm days, but they mostly eat nuts such as acorns, beech nuts, and pecans. Red-headed Woodpeckers cache food by wedging it into crevices in trees or under shingles on houses. They store live grasshoppers, beech nuts, acorns, cherries, and corn, often shifting each item from place to place before retrieving and eating it during the colder months.

Nesting Facts

Clutch Size 3–10 eggs - Number of Broods 1-2 broods - Egg Length 1 in. Incubation Period 12–14 days - Nestling Period 24–31 days - Egg Description Pure white - Condition at Hatching Naked, with eyes closed. Nest Description Both partners help build the nest, though the male does most of the excavation. He often starts with a crack in the wood, digging out a gourd-shaped cavity usually in 12–17 days. The cavity is about 3–6 inches across and 8–16 inches deep. The entrance hole is about 2 inches in diameter.

Nest Placement - Cavity

The male selects a site for a nest hole; the female may tap around it, possibly to signal her approval. They nest in dead trees or dead parts of live trees—including pines, maples, birches, cottonwoods, and oaks—in fields or open forests with little vegetation on the ground. They often use snags that have lost most of their bark, creating a smooth surface that may deter snakes. Red-headed Woodpeckers may also excavate holes in utility poles, live branches, or buildings. They occasionally use natural cavities. Unlike many woodpeckers, Red-headed Woodpeckers often reuse a nest cavity several years in a row.

Behavior - Fly catching

Red-headed Woodpeckers climb up tree trunks and main limbs like other woodpeckers, often staying still for long periods. They are strong fliers with fairly level flight compared to most woodpeckers. They often catch insects on the wing. Prospective mates play “hide and seek” with each other around dead stumps and telephone poles, and once mated they may stay together for several years. Both males and females perform aggressive bobbing displays by pointing their heads forward, drooping their wings, and holding their tails up at an angle. They are territorial during the breeding season and often aggressive and solitary during the winter. Red-headed Woodpeckers are quick to pick fights with many other bird species, including the pushy European Starling and the much bigger Pileated Woodpecker. Their predators include snakes, foxes, raccoons, flying squirrels, Cooper’s Hawks, Peregrine Falcons, and Eastern Screech-Owls.

Conservation status; Threatened

Red-headed Woodpeckers have declined on average by 2.7 percent per year from 1966–2010, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey—suggesting a cumulative drop of some 70 percent over the whole period. The most severe losses have been in Florida and the Great Lakes, with only scattered areas of modest increase evident in parts of Alabama, Georgia, the Northeast, and the Midwest. Red-headed Woodpeckers were common to abundant in the nineteenth century, probably because the continent had more mature forests with nut crops and dead trees. They were so common that orchard owners and farmers used to pay a bounty for them, and in 1840 Audubon reported that 100 were shot from a single cherry tree in one day. In the early 1900s, Red-headed Woodpeckers followed crops of beech nuts in northern beech forests that are much less extensive today. At the same time, the great chestnut blight killed virtually all American chestnut trees and removed another abundant food source. Red-headed Woodpeckers may now be more attuned to acorn abundance than to beech nuts. Though the species was common in towns and cities a century ago, it began declining in urban areas as people started felling dead trees and trimming branches. After the loss of nut-producing trees, perhaps the biggest factor limiting Red-headed Woodpeckers is the availability of dead trees in their open-forest habitats. Management programs that create and maintain snags and dead branches may help Red-headed Woodpeckers. Although they readily excavate nests in utility poles, a study found that eggs did not hatch and young did not fledge when the birds nested in newer poles (3–4 years old), possibly because of the creosote used to preserve them. In the middle twentieth century Red-headed Woodpeckers were quite commonly hit by cars as the birds foraged for aerial insects along roadsides.

Credits;

- The Red-headed Woodpecker is one of only four North American woodpeckers known to store food, and it is the only one known to cover the stored food with wood or bark. It hides insects and seeds in cracks in wood, under bark, in fenceposts, and under roof shingles. Grasshoppers are regularly stored alive, but wedged into crevices so tightly that they cannot escape.

- Red-headed Woodpeckers are fierce defenders of their territory. They may remove the eggs of other species from nests and nest boxes, destroy other birds’ nests, and even enter duck nest boxes and puncture the duck eggs.

- The Red-headed Woodpecker benefited from the chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease outbreaks of the twentieth century. Though these diseases devastated trees they provided many nest sites and foraging opportunities for the woodpeckers.

- The striking Red-headed Woodpecker has earned a place in human culture. Cherokee Indians used the species as a war symbol, and it makes an appearance in Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, telling how a grateful Hiawatha gave the bird its red head in thanks for its service.

- The Red-headed Woodpecker has many nicknames, including half-a-shirt, shirt-tail bird, jellycoat, flag bird, and the flying checker-board.

- Pleistocene-age fossils of Red-headed Woodpeckers—up to 2 million years old—have been unearthed in Florida, Virginia, and Illinois.

- The Red-headed Woodpecker was the “spark bird” (the bird that starts a person’s interest in birds) of legendary ornithologist Alexander Wilson in the 1700s.

- The oldest Red-headed Woodpecker on record was banded in 1926 in Michigan and lived to be at least 9 years, 11 months old.

Habitat

Open Woodland

Red-headed Woodpeckers breed in deciduous woodlands with oak or beech, groves of dead or dying trees, river bottoms, burned areas, recent clearings, beaver swamps, orchards, parks, farmland, grasslands with scattered trees, forest edges, and roadsides. During the start of the breeding season they move from forest interiors to forest edges or disturbed areas. Wherever they breed, dead (or partially dead) trees for nest cavities are an important part of their habitat. In the northern part of their winter range, they live in mature stands of forest, especially oak, oak-hickory, maple, ash, and beech. In the southern part, they live in pine and pine-oak. They are somewhat nomadic; in a given location they can be common one year and absent the next.

Food

Omnivore

Red-headed Woodpeckers eat insects, fruits, and seeds. Overall, they eat about one-third animal material (mostly insects) and two-thirds plant material. Their insect diet includes beetles, cicadas, midges, honeybees, and grasshoppers. They are one of the most skillful flycatchers among the North American woodpeckers (their closest competition is the Lewis’s Woodpecker). They typically catch aerial insects by spotting them from a perch on a tree limb or fencepost and then flying out to grab them. Red-headed Woodpeckers eat seeds, nuts, corn, berries and other fruits; they sometimes raid bird nests to eat eggs and nestlings; they also eat mice and occasionally adult birds. They forage on the ground and up to 30 feet above the forest floor in summer, whereas in the colder months they forage higher in the trees. In winter Red-headed Woodpeckers catch insects on warm days, but they mostly eat nuts such as acorns, beech nuts, and pecans. Red-headed Woodpeckers cache food by wedging it into crevices in trees or under shingles on houses. They store live grasshoppers, beech nuts, acorns, cherries, and corn, often shifting each item from place to place before retrieving and eating it during the colder months.

Nesting Facts

Clutch Size 3–10 eggs - Number of Broods 1-2 broods - Egg Length 1 in. Incubation Period 12–14 days - Nestling Period 24–31 days - Egg Description Pure white - Condition at Hatching Naked, with eyes closed. Nest Description Both partners help build the nest, though the male does most of the excavation. He often starts with a crack in the wood, digging out a gourd-shaped cavity usually in 12–17 days. The cavity is about 3–6 inches across and 8–16 inches deep. The entrance hole is about 2 inches in diameter.

Nest Placement - Cavity

The male selects a site for a nest hole; the female may tap around it, possibly to signal her approval. They nest in dead trees or dead parts of live trees—including pines, maples, birches, cottonwoods, and oaks—in fields or open forests with little vegetation on the ground. They often use snags that have lost most of their bark, creating a smooth surface that may deter snakes. Red-headed Woodpeckers may also excavate holes in utility poles, live branches, or buildings. They occasionally use natural cavities. Unlike many woodpeckers, Red-headed Woodpeckers often reuse a nest cavity several years in a row.

Behavior - Fly catching

Red-headed Woodpeckers climb up tree trunks and main limbs like other woodpeckers, often staying still for long periods. They are strong fliers with fairly level flight compared to most woodpeckers. They often catch insects on the wing. Prospective mates play “hide and seek” with each other around dead stumps and telephone poles, and once mated they may stay together for several years. Both males and females perform aggressive bobbing displays by pointing their heads forward, drooping their wings, and holding their tails up at an angle. They are territorial during the breeding season and often aggressive and solitary during the winter. Red-headed Woodpeckers are quick to pick fights with many other bird species, including the pushy European Starling and the much bigger Pileated Woodpecker. Their predators include snakes, foxes, raccoons, flying squirrels, Cooper’s Hawks, Peregrine Falcons, and Eastern Screech-Owls.

Conservation status; Threatened

Red-headed Woodpeckers have declined on average by 2.7 percent per year from 1966–2010, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey—suggesting a cumulative drop of some 70 percent over the whole period. The most severe losses have been in Florida and the Great Lakes, with only scattered areas of modest increase evident in parts of Alabama, Georgia, the Northeast, and the Midwest. Red-headed Woodpeckers were common to abundant in the nineteenth century, probably because the continent had more mature forests with nut crops and dead trees. They were so common that orchard owners and farmers used to pay a bounty for them, and in 1840 Audubon reported that 100 were shot from a single cherry tree in one day. In the early 1900s, Red-headed Woodpeckers followed crops of beech nuts in northern beech forests that are much less extensive today. At the same time, the great chestnut blight killed virtually all American chestnut trees and removed another abundant food source. Red-headed Woodpeckers may now be more attuned to acorn abundance than to beech nuts. Though the species was common in towns and cities a century ago, it began declining in urban areas as people started felling dead trees and trimming branches. After the loss of nut-producing trees, perhaps the biggest factor limiting Red-headed Woodpeckers is the availability of dead trees in their open-forest habitats. Management programs that create and maintain snags and dead branches may help Red-headed Woodpeckers. Although they readily excavate nests in utility poles, a study found that eggs did not hatch and young did not fledge when the birds nested in newer poles (3–4 years old), possibly because of the creosote used to preserve them. In the middle twentieth century Red-headed Woodpeckers were quite commonly hit by cars as the birds foraged for aerial insects along roadsides.

Credits;

- Smith, K. G., J. H. Withgott, and P. G. Rodewald. 2000. Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus). In The Birds of North America, No. 518 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America Online, Ithaca, New York.

- IUCN. 2012. Red List of Threatened Species (ver. 2012.1).

- Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, J.E. Fallon, K.L. Pardieck, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W.A. Link. 2011. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966–2010. Version 12.07.2011. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD.

- USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. 2011. Longevity Records of North American Birds.

All woodpeckers nest in tree cavities, but northern flickers, red-headed woodpeckers and downy woodpeckers also may take up residence in bird houses.

Northern flicker requirements: 7” x 7” x 18” high; hole: 2-1/2”, centered 14” above the floor; color: natural; placement: 8–20’ high on tree trunk; nesting material: 4” of wood shavings on floor.

Red-headed woodpecker requirements: 6” x 6” x 15” high; hole: 2”, centered 6–8” above the floor; placement: 8–20’ high on tree trunk; nesting material: 4” of wood shavings on floor.

Downy woodpecker requirements: 4” x 4” x 10” high; hole: 1-1/4”, centered 6–8” above the floor; placement: 8–20’ high on tree trunk; nesting material: 4” of wood shavings on floor.

Habitat: Because woodpeckers are woodland birds, they will be more likely to occupy birdhouses that are mounted on the trunks of mature trees in the middle of woodlands.

Northern flicker requirements: 7” x 7” x 18” high; hole: 2-1/2”, centered 14” above the floor; color: natural; placement: 8–20’ high on tree trunk; nesting material: 4” of wood shavings on floor.

Red-headed woodpecker requirements: 6” x 6” x 15” high; hole: 2”, centered 6–8” above the floor; placement: 8–20’ high on tree trunk; nesting material: 4” of wood shavings on floor.

Downy woodpecker requirements: 4” x 4” x 10” high; hole: 1-1/4”, centered 6–8” above the floor; placement: 8–20’ high on tree trunk; nesting material: 4” of wood shavings on floor.

Habitat: Because woodpeckers are woodland birds, they will be more likely to occupy birdhouses that are mounted on the trunks of mature trees in the middle of woodlands.